One day a few years ago, on my way to the silversmith I walked past a store in Albuquerque's Old Town, the Spanish Colonial settlement founded in the early 1700s by colonizers pushing up from Mexico City. I had only recently started coming back to this area, although as a young girl I spent many a summer day in Old Town with friends, walking the narrow roads and shopping the small adobe homes-turned-shops. Back then we would buy blown glass figurines and tumbled rocks. Yet Old Town was also the most extensive source of Native American jewelry, sold in shops and by Navajo and Zuni Native Americans sitting under a portal on the square or plaza. For most Albuquerqueans of late, Old Town had become the place to take your out-of-state visitors to buy souvenirs.

All that changed for me when I began buying and selling turquoise jewelry myself. My silversmith was in Old Town and many a piece I bought was in need of a stone replacement or ring resizing. Suddenly I found myself making trips to this tourist destination at least once a week to drop off or pick up pieces, and that's what took me past a large store advertising Native American jewelry. On a whim, I decided to go inside.

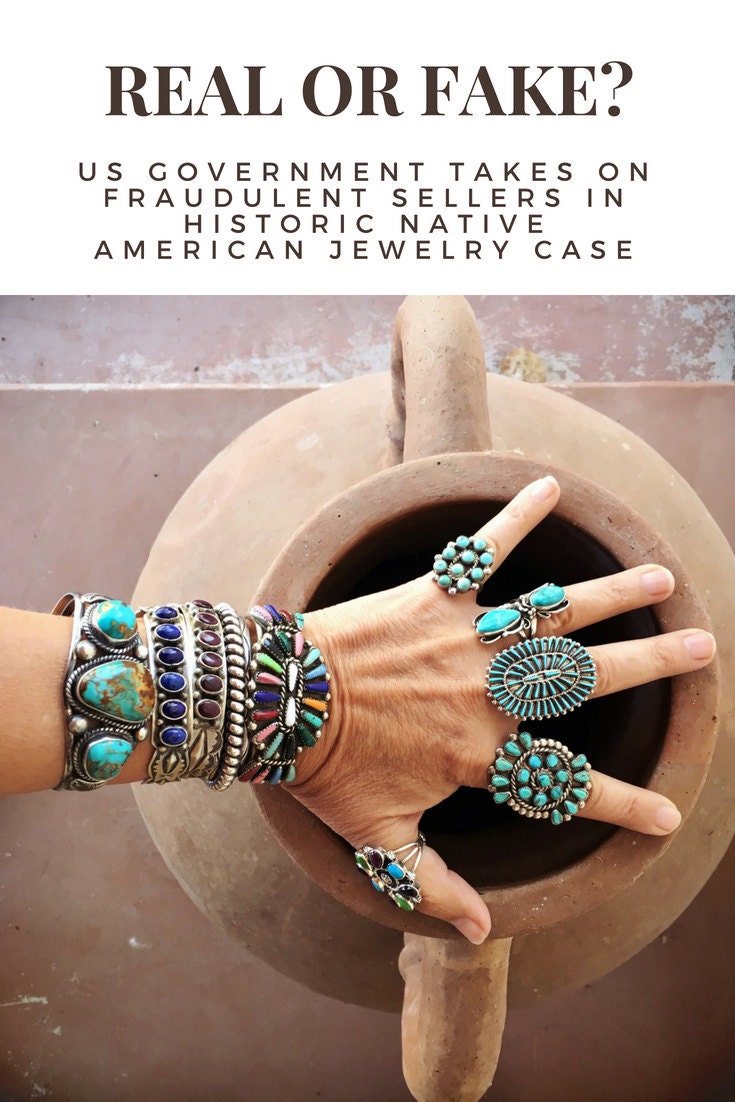

Thousands of pieces of turquoise and silver jewelry filled glass cases all around the shop, most at surprisingly low prices. I asked to see a few, and they carried hallmarks on the back, those initials indicating the Native American artist who made the piece. They also had sterling silver stamps. In a hurry and somewhat wow’d by the low cost, I bought a set of Navajo Pearls and a turquoise pendant to go with it. I paid and headed out to my silversmith’s shop.

Later that night while examining my buys, I noticed the silver on the Navajo Pearls looked odd. I hadn't been working with silver and turquoise as much as I have since, but already I was starting to recognize the difference between real and fake silver. This silver had a faint blue almost gun metal hue, not the white-silver look of sterling. I pulled out my silver test and placed a tiny dot of liquid near the 925 stamp. That's the mark indicating 92.5% silver content--the definition of "sterling silver." The dot from my tester kit turned green, which was exactly the color it would turn if the metal was nickel, not silver. Now a bit panicked--these were well-priced pieces yet not cheap--I pulled out the pendant and compared it to old pieces of mine. Unlike the old pieces, this one had rough edges along the silver foundation, as if it punched out by a metal cookie cutter and not filed down by hand.

I eventually returned the pieces but flash forward to today and it turns out the walls of lit cases in that shop were actually filled with fake Native American jewelry. Unbeknownst to me at the time I bought the pieces, the shop was then under investigation by the federal government in an extensive sting operation. And the jewelry I bought? Made in the Philippines and passed off as Navajo, complete with fake Native American artist stamps! The investigation was called "Operation Al Zuni" and undertaken by a section of the US Fish and Wildlife Services. It targeted Al Zuni Global Jewelry, which called itself the "largest wholesaler of Indian jewelry." Run by Palestinian families, the company imported counterfeit Native American jewelry and sold it through an extensive network of stores in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Gallup, Scottsdale, Tucson, Aspen, San Diego, and cities in Texas and even as far as Virginia and Alaska!

This was the first ever charge based on a 1935 federal act--Indian Arts and Crafts Act or IACA—making it illegal to pass off non-Native American arts and crafts as Native made. Penalties for first-time violaters can include up to five years of jail time plus $250,000 in fines. Which means that the Al Zuni Global Jewelry owner and his main middleman, the two charged, could be the first people sent to prison under the law.

This company and network have been producing so-called Native jewelry since 1972, and had been brought to the attention of federal investigators as early as 1994. But the New Mexico stores were not raided until 2015. A shipment was intercepted by federal investigators in 2012, marked with invisible ink, which allowed undercover agents to confirm by using ultraviolet light that the jewelry being sold as Navajo was actually the same imported in from the company.

Dubbed "the biggest fake Native American Art conspiracy" by The National Geographic, this crack-down has been followed closely by Native Americans and non-Natives throughout the Southwest, and none moreso than in Albuquerque. The trial for sentencing of two of the main players began just a few days ago, on May 10. As it stands, it looks as though there will be prison time involved, which could be up to five years for each individual unless a deal is made. Grassroots groups are calling for the toughest sentencing possible. It is an understatement to say that this network has negatively affected authentic Native American jewelers and craftsmen and women. It is estimated that just one of the companies that is part of the network imported over $11 Million in fake jewelry.

I'll continue to monitor this case, as the sentencing is not over. What I can say is that stores and vendors are on alert and more aware now than ever before. I feel one thousand times more confident buying now that this case has exploded. Yes, the frauds may make their way back onto the scene, and I'm sure there are plenty out there who haven't been taken off the scene. But fraudulent dealers are now seeing consequences to their actions.

To learn more about this important case, check out the Smithsonian’s Investigators Crack Down on Fraudulent Native American Jewelry, and artnet news How Investigators Used Invisible Ink to Unmask the Largest-Ever Native American Art Fraud Conspiracy.